How ‘Wanderstop’ Devs Ivy Road Create Friction in ‘a Mundanity Simulator’

After releasing The Stanley Parable and The Beginner’s Guide, Ivy Road co-founder Davey Wreden was, in his words, “extraordinarily burnt out.” Although this wasn’t the sole impetus behind the creation of Wanderstop, a cozy tea-making game about intentional rest and recovery, Wreden says it was certainly a factor in the game’s initial development.

“There are so many games and pieces of media that are important to me because they feel like a real thing that exists in the world,” Wreden tells site. “That sort of blended with this feeling of, ‘Wow, I really need to rest and I really need to find stability and I need to find something grounding that I can do with myself.’

“Those ideas merged and I thought it would be really innovative and new and different to make a game like Animal Crossing—which was the reference point—that takes its promises and blue-sky optimism and marries that with game design that doesn’t devolve into resource grind,” he continues. “I always felt that the promise of Animal Crossing was just existing and being in a place, but in the actual gameplay, especially as the series goes on, the games become progressively more about resource grinding.”

Wanderstop is the final result of that concept. The player controls Alta, a fighter who winds up at a magical tea shop with no memory of how she got there and no idea why she suddenly can’t lift her sword. As she works with the shop owner, Boro, and meets its various customers, she slowly discovers what happened to her and what true recovery looks like. It isn’t easy or pretty or straightforward, no matter how hard she tries to make it so.

Creating Friction in Wanderstop

Wreden and Ivy Road co-founder Karla Zimonja (Gone Home, Tacoma) say one of the major challenges they faced in developing Wanderstop was creating friction in what’s ultimately “a mundanity simulator” without creating time-based stress for the player.

“We want their time to pass, but we don’t want it to have the feeling of something you’re fighting,” Wreden says. “We want it to feel like something you’re surrendering to.”

“In a lot of these life sim games, you’re trying to get up to the point right before you fall down unconscious to get as much done as you possibly can during the day and then make it home or whatever,” Zimonja says. “That is not the vibe we were going for.”

Speaking to Wreden, Zimonja adds, “I remember you rendering it at one point as being kind of like, ‘No, I made this environment. I set it up the way I wanted. I am just going to hang out here until I feel ready to leave. You cannot force me.’ [Players] aren’t going to be like, ‘Oops, I walked into a cut scene.’ None of that. It’s just like, no, if you want to hang out and plant every seed you have and arrange the mugs how you want it, you are allowed. You can hang out in there.”

Time in Wanderstop primarily moves forward through character conversations and Alta’s actions, the timing of which is entirely determined by the player. The only in-game timer is for drying tea leaves, and even that can be left alone. When the leaves are ready to be brewed, they’ll simply sit in their container, ready for the taking. Nothing burns or collapses; no one gets impatient and leaves. Even the businessmen who demand coffee when there are no beans available are happy to wait until coffee becomes a possibility, which could be forever if Alta opts to just keep making tea.

Since time doesn’t provide friction in Wanderstop, Ivy Road had to introduce it in other ways.

“If we take that initial promise of something like Animal Crossing, how do we ask players to be in the moment with it and not be trying to optimize? My initial idea was, ‘Events will be random so you can’t control them,'” Wreden says. “It became clear pretty quickly that wasn’t an option. We might get around the optimization problem, but it would create a new problem: Generative content is super hard to make and usually really boring unless you’re a genius game designer.”

Wreden notes there is already inherent friction in a “cozy game” with a heavy story: “The cozy gameplay and the mundanity is this safe nest that couches a dark and difficult and uncomfortable narrative, and the nesting of that darkness maybe creates the feeling of comfort for people to be able to be willing to go into it and explore it.”

Zimonja adds, “You venture out into the difficult portions of the game and then you’re like, ‘Okay, I’m just going to plant some things for a little while.’ Sort of like real life. You do something hard and you’re like, ‘What if I hung out at home and listened to a podcast and pet a cat?’ The cycle of explore and calm down.”

There’s additional tension in the gameplay itself. Although there’s plenty to do in Wanderstop—including fetch and discovery quests—Wreden and Zimonja didn’t want players to feel pressured into doing things at a breakneck pace. They also worked to balance the characters who provided “little tasks” for Alta and characters who entered the story for other purposes, trying to create both intrinsic and extrinsic value in the story.

“We do want to meet players halfway. We want to be like, ‘Hey you. We want you to understand what is occurring here, what’s important and what’s not important and what you can do. We want that. We one hundred percent want that.’ What does it mean a player? That’s such a big range of things,” Zimonja explains. “There’s my dad who would be very grateful to have the directions to do things. There’s me who would be like, ‘No, shut up. I’ll figure it out myself.’ Who are we pleasing here? And even if you go with whatever the numerically constructed gamer median is, even then you’re narrowing your audience to just that. That doesn’t make it any easier for other people to approach.”

“I struggle with that so hard,” Wreden says. “Depending on the day, I’ll be like, ‘It needs to be the pure version and f**k all of people who need tasks to do.’ And then the next day, it’s ‘No, no, no. I want them to be happy. I want it to feel enough like a video game that they can consume. I don’t want them to reject it outright.”

“Even those specific things like checking off tasks on a list—that’s an extrinsic reward. We do that to motivate ourselves. In the real world, we do to-do lists, and we’re like, ‘I feel accomplished. I checked off all the things,'” Zimonja says. “It’s not necessarily, ‘I feel accomplished. I did those tasks.’ It’s checking them off. That inherently is a little at odds with what we were trying to do here, which is wanting players to find the intrinsic enjoyment in the task itself. The minute you say, ‘Do the thing and it will get checked off,’ that’s an extrinsic layer. There’s a certain amount that’s like an olive branch to people who really want it.”

Wreden and Zimonja’s Favorite Wanderstop Characters

Alta can converse with Boro, Wanderstop’s owner, and the various customers who come and go from the shop in each cycle of the game. The first cycle introduces Gerald, a wannabe knight, and the Demon Hunter, who’s new to the job.

“For most of this game’s development cycle, Cycle One was the only one that existed and then the last four came into being very quickly,” Wreden explains. “Demon Hunter’s story was this sprawling thing that went on for hours and hours. We had someone come over and play it, and I think Cycle One took them four or five hours. That was like, ‘Whoa, this is way out of control.'”

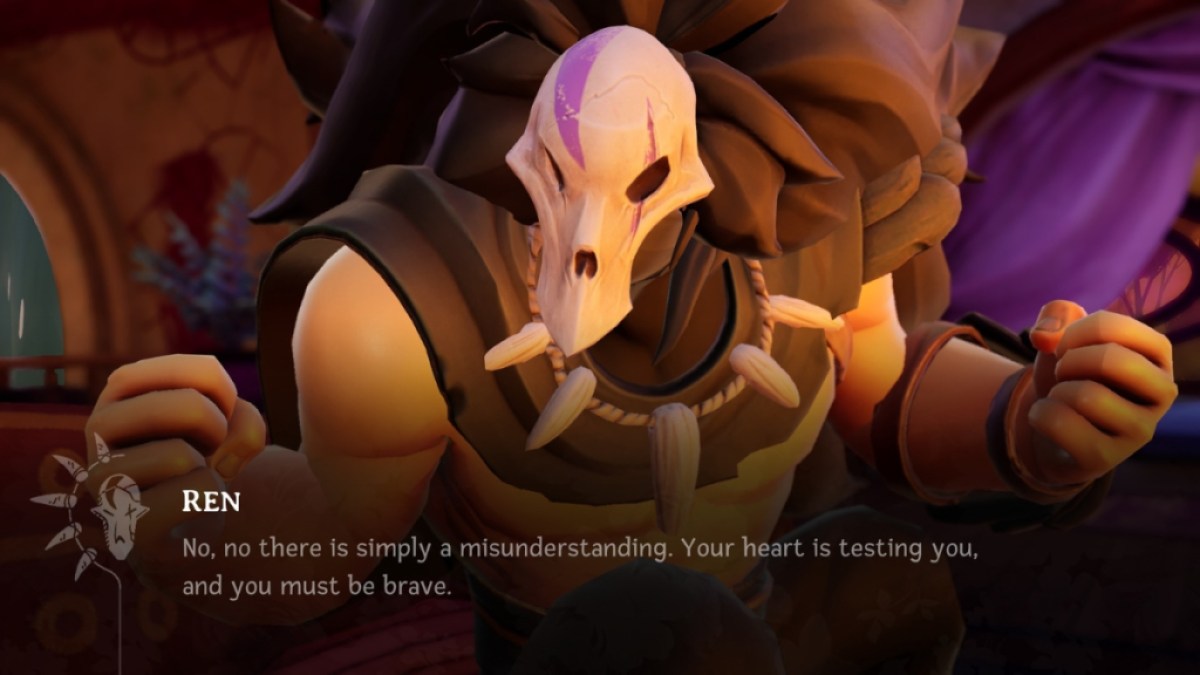

In this way, Demon Hunter and Gerald were “gristle for the machine,” per Wreden. They’re also typical for the kinds of characters we expect to encounter in cozy games. But as Zimonja points out, these two characters were created before the developers realized how they wanted customers to support and play into Alta’s journey in Wanderstop. Characters who come later, like the fighter Ren and the child Monster, hold a very different level of importance in the story and for the developers.

“Ren is one of my favorite parts of this game because he’s such a terrific reflection. He’s a slightly different version of what Alta has and the way he plays it… Alta’s like, ‘I want that so bad.’ He’s the embodiment of that and it’s so clean. His scenes aren’t long. He doesn’t talk a lot, but the impact per amount of screen time for him is very good. I’m proud of him,” Zimonja says.

Ren went through significant changes in the writing process as well. He was initially a pure Alta fanboy, but in his final version, he mansplains fighting and recovery to Alta and diminishes her struggle because it doesn’t fit the vision he has of her in his mind. Although his presence in her life is ultimately short-lived, his impact lasts. The same goes for Monster, who Alta struggles to do right by because of her trauma.

“I don’t think that Monster is one of the beloved characters from this game, but she’s really, really meaningful to me,” Wreden says. “There’s a scene where she draws a picture on the wall of Alta winning a fight and then they have a conversation where Monster asks, ‘How do you get yourself to want things more?’

“I remember I put it in the script and implemented it and then the artists do a layer on lighting and the animators add animation and Daniel [Rosenfeld] adds music. I remember there was a point where I opened up the scene and played it and every single element about that scene right then was perfect to me. There’s nothing I would change about it.”

As for the overall takeaway from Wanderstop, Wreden says, “I would hope that people are able to play this thing and come away from it and go, ‘Oh, okay, this is a lot more complicated than just I’m burnt out and I need to rest.’ Rest is important. But one of the first steps in getting better is realizing that the most immediate, simple, in front of your face answer [for recovery] is usually the one that’s been put there to keep you kind of penned in. … What does it mean to confront that and look in the mirror?”

Wanderstopis available forPlayStation,Xbox, andPC via Steam.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

-

Get free Primogems, Mora, Experience, and more with these November 2024 Genshin Impact codes, 5.1 livestream codes, and find out how to redeem active codes.

Get free Primogems, Mora, Experience, and more with these November 2024 Genshin Impact codes, 5.1 livestream codes, and find out how to redeem active codes. -

Top 5 Mods for Metaphor ReFantazio

If you are bored with playing the vanilla version of Metaphor ReFantazio, you can check out these five mods. -

How to win the costume contests in Roblox Haunt 2024

Struggling with your submissions for Roblox's The Haunt event in 2024? Check out our guide on using Dress to Impress to create your captures! -

Dragon Age The Veilguard walkthrough, tips and tricks

Our walkthrough for Dragon Age: The Veilguard with some handy tips and tricks, with guides for puzzles, bosses, companions, equipment, romance, and more!